From Cocteau’s diary. Lines written in Vallauris while he

was staying with Picasso. Picasso was working mostly with ceramics at this

time, after having finished La Guerre et

La Paix, and Cocteau made plates of his own in the studio. He would also go on to start the plans for The Birth of Pegasus. This time is split by a press tour through

Italy, (with the usual grievances of mediocre journalists,

superficial admirers, and the exhausting demands of the press). Cocteau then leaves for the 1953 Cannes

Film Festival, in which he serves as president of the jury. He admires

Clouzot’s Wages of Fear and Disney’s Peter Pan, though is mostly reluctant

about his responsibilities as president. This excerpt begins about two months earlier, on the first day of his stay with Picasso.

24 Feb 1953

Lunched in Vallauris. Picasso was at the studio where I

later went to meet him with Françoise. Picasso opens a locked door, we enter,

and there’s Guerre et Paix (War and

Peace). My first impression is the nave of a church, and that walking in one should take off one's hat. I, anyway, take off mine. It’s the work of youth,

of incredible violence. Equilibrium between zeal and calm. A marriage between Le Bain turc* and L’entrée des croises a Constantinople**. No form is realist but

everything is true, internally true, which is all that counts. And, leaving the

room, reality seems pallid, grey, ugly, dead, extinguished.

The huge

piece, to be shown in Rome with a hundred other canvases†, will, rightly, end

up in the Vallauris chapel‡. The pictures [18 panels of hardboard making up

two 9-board pictures] will be curved so that they meet at the top of the chapel

(the curve beginning from very low). From right to left: the first panel

shows War in his chariot, or carriage, or horse-drawn coach, carrying on his

back a sort of basket made of black lace, full of skulls. The figure holds in

his left hand a disc covered with microbes and surrounded by flying microbes.

His brandishes with his right hand a bleeding glaive. The horses of War trample a large,

flaming book (the library of Alexandria). Above the horse, dark warriors’ silhouettes

shake the shadows of their armour. Facing the horses stands an immense nude

figure (Peace), holding a lance and a shield on which one can make out the face

of a woman, on which Picasso has drawn a dove with its wings open. On the left

picture, a family, all nude, is gathered on the grass. A woman breastfeeds her

baby while reading. One man is blowing on a pot of soup. Another is engaged in

some mysterious study. To their left, a child drives a plough pulled by a

white-winged horse. Then, dancing women. A faun plays the flute, his legs crossed

over a shell. A kind of swimming or flying child with an owl on his head forms

the centre of balance of a set of three scales, at the ends of which are

suspended a cage of fish, a bowl of birds, and an hourglass.

The whole thing is

painted freely, thickly, with large strokes. One is offered implicitly the

drafts and redrafts. Picasso has left a trail. He says, “One doesn’t advise

someone unhappy to wipe his tears.”

He explains to me

what he’s done, undone and redone. He says, “It’s always the thieving magpie

and the prodigal child – fable.” After lunch at La Galloise I return to the

studio and Picasso, having shown me the canvases of Françoise and the kids, takes me to the Ramiés’ pottery

studio.

He tells me a story of

great importance to him, and says, “You should make something with it.” He’d

just painted a face on a plate and noted its resemblance to Huguette, the wife

of one of the potters. The face had a beard. “Alright,” he said. “Since it’s

Huguette, let’s take out the beard.” He does this and the face no longer looks

like Huguette. He puts the beard back and Huguette reappears. I’ll add that

this young woman is pregnant.

He shows me one of

his innovations in pottery, which consists of sketching on the clay with

coloured crayons. Then, he arranges them in the kiln after a “travail de liquide”

(any potters out there who know what this is?). The pastel or crayon settles

and, to the eye, still appears as pastel and crayon.

I’m back to see Françoise

at the house. Excellent canvasses by Françoise. Little girls dancing madly, monsters

before groups of male and female musicians.

Picasso over dinner:

“I joined the communist party because I thought I’d find a family. In effect, I

found a family, with all the bullshit that that means. The son who wants to

become a lawyer, the one who wants to win the Prix de Rome. Never join such a

family.”

“There’s also,” adds

Françoise, “the fact that the communists only respect people outside the Party.”

I ask Picasso what

the communists think of Guerre et Paix.

“They approve. It’s up to me to put them in line.”

Picasso gives me a tablemat

which he decorated at the studio. Madame Ramié gives me a large plate. The head

of a ram in relief, very beautiful.

I say to Picasso:

“Youth lacks heroism. It’s funny that no young person has managed to kill you.”

He responds: “I’ve taken precautions.”

That’s understandable,

since any painter next to his Guerre et

Paix (and I mean any painter of professed boldness) seems weak, ridiculous.

Picasso: “I don’t

know what I’m going to do or what I am doing. And if in the evening I want to

discuss what I’ve done with Françoise, nothing comes to mind. Painting is the work of the blind.”

About Chagall,

working in pottery: “I give him all my secrets and he thinks I’m trying to

sabotage him. If I sold them to him, he’d believe me.”

About Stravinsky

(regarding our feud): “He’ll never get that it’s not the same between him and

you as between you and me.”

On Oedipus Rex††: “You’re the reason for

the scandal, not Stravinsky. He’s able to make more and more beauty, but no

longer to make scandals.”

We’re preparing a

colour book which will show the whole of Guerre

et Paix, including the smallest details. [Fernand] Mourlot is in Vallauris.

There’s nothing that Picasso invents which doesn’t immediately become

“historic.”

There are only

children (exhibition at Muratore’s gallery in Nice) who obtain such power and

such freedom. That Picasso should form the bridge between this childish power

and the calculations and science of painting is a true miracle.

Guerre et Paix is, once again, a mighty insult to habit. Above

all to Rome’s. Hence his delight to have it shown there.

I say to Picasso,

“You’re winged horse resembles the horse in Greco’s Cardinal Tavera (currently in the Hospital de Tavera in Toledo).”

Picasso: “There’s no

queen bee, rather there’s one chosen randomly and the others feed it until it

becomes larger and more important than them.”

He must be right. By

chance for Great Britain, Queen Elizabeth is a queen, but it was random. The

Japanese men I met yesterday told me that Kikugoro [a famous actor of Kabuki in

Tokyo, whom Cocteau met in 1936] is dead (he was Kikugoro IV). Kikoguro V isn’t

his son. If the actor esteems his son unable to succeed him, he adopts a young

actor who deserves to.

(…)

Yesterday, Picasso

spoke of opium. “Besides the wheel, it’s all that man’s discovered.” He regrets

that people can’t smoke freely and asks me if I still smoke habitually. I say

no, and that I regret it as much as he does. “Opium,” he adds, “provokes goodness.

The proof is that no smoker is greedy about his privilege. He wants everyone to

smoke.” It’s impossible to be less “in line” than Picasso. Really, he’s a

member of the communist party without being a communist. We’re too far from the

communists who would kill their fathers and mothers in the name of the cause.

Let’s not forget to

mention that the “Picassian” creation is of a diabolical order. The devil

cannot create, only destroy. One could say that Picasso’s creation is a

destruction. Perhaps, but there can never be creation without destruction, the

destruction of that which it is. That Picasso disturbs other painters, crushes

them, that this raptor devours them, is precisely it. If they dream of his

death, they’re wrong to. His works will be more active than the man. Though his

death would be a catastrophe. Such genius cannot be reproduced.

(…)

Picasso. He’s

established like dogma that anything seeming “well made” betrays a certain will

to aesthetics, a lack of elegance of the spirit. He thus scribbles a face on a

crowd of well made faces. This “badly made,” which for him is right and which

comes after a thousand investigations, deceives the youth who have no inkling

of the rhythm of his work. In this way, he “misplaces” the scribbles and

discredits, in advance, those able to contradict him, and whom we take for

aesthetes. He’s a belligerent warrior, skilled in every ruse, knowing every parry,

agile as a matador. Matisse can’t say five words without mentioning his name.

He’s the idol and the nightmare of painters. Unique situation. Furthermore, the

money committed to him staves off his ruin. He is sovereign, against painters,

politics, and all.

************

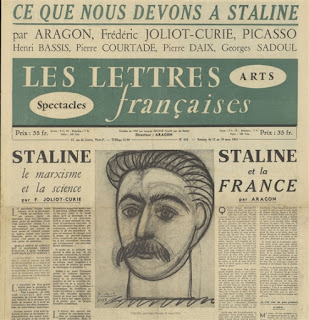

On the 12th

of March, Louis Aragon published an edition of Les Lettres Françaises in homage to the recently deceased Stalin,

including a portrait by Picasso, which met

heavy criticism. Cocteau documents this, and explains that Picasso – who in the

diary only speaks favourably of Stalin – was rushed by Aragon to finish the

portrait, leading him to sketch out what he did within five minutes.

Aside from pockets of critics complaining of a painter exploiting his celebrity, every sector of communist France had its ideas on how it would have praised

Stalin in a different light than Aragon had. The magazine was pressured to publish

in its next edition a spread with letters from the backlash, from which Cocteau

paraphrases the general sentiment: “It was necessary to show the genius, the

goodness, the paternal kindness, the humour, the nobility, etc., of our Stalin.”

Cocteau himself jots down a few reflections on communism throughout all volumes of his journals, but

especially around this time, stimulated by his stay with Picasso and Stalin’s

recent death. The tone is consistent with his scepticism of any institution not

immediately artistic. Reflecting on Picasso’s place in the controversy around

the Lettres Françaises edition, he

notes, “When my play Bacchus was

attacked by the church, it was the communists who came to my defence. Now that

Picasso’s sketch is being attacked by the communists, it’s the church which comes

to his defence.”

Below is the front page

of the 12th March 1953 Lettres

Françaises, with Picasso’s sketch.

* Ingres, 1862.

** Delacroix, 1840.

† Part of a retrospective of his “political” works

(including Guernica, le Charnier, and Massacre en Corée), which toured Italy.

‡ Currently the National Picasso Museum, where one can find Guerre et Paix.

†† Opera by Stravinsky with a libretto by Jean Cocteau.

No comments:

Post a Comment